Better standards.

Better-informed decisions.

Companies, not-for-profit organizations, and governments use accounting standards as a foundation for providing users of financial statements with relevant information. That information helps investors, lenders, citizens, and others make important decisions about whether to provide capital, lend or donate money, or whether or not to support a voter referendum.

It stands to reason, then, that better accounting standards help financial statement users make better-informed decisions.

The pursuit of better standards informs everything we do. The Financial Accounting Foundation (FAF) and its standard-setting Boards—the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) and the Governmental Accounting Standards Board (GASB)—are committed to fostering standards that result in information that is relevant, representationally faithful, and reflective of the financial condition of an organization or government.

What follows in these pages is a snapshot of how we fulfilled this objective in 2016. For the FASB, it meant issuing standards that give investors better information about an institution’s expected credit losses and lease obligations. For the GASB, it meant educating stakeholders about standards that enhance transparency around retirement obligations and developing an improved financial reporting model. And for the FAF, it meant supporting the Boards in these efforts while ensuring they follow a robust, inclusive due process.

Investors and citizens trust financial statements that follow Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP). Through our work, we aim to continue to earn that trust through standards that help all our stakeholders make better-informed decisions.

Major Achievements in 2016

Messages from the FAF, FASB, and GASB Leaders

Financial Review

2016 Sources of Revenues

- 53%FASB Accounting Support Fees

- 18%GASB Accounting Support Fees

- 29%Net Subscriptions & Publications

2016 Expenses

- 78%Program — Standard Setting

- 22%Support

About Us

Financial reporting is the language that communicates information about the financial condition and operational results of a company (public or private), not-for-profit organization, or state or local government. Accounting standards determine how those financial statements are prepared. The standards are known collectively as Generally Accepted Accounting Principles—or GAAP.

The Financial Accounting Foundation (FAF) is the independent, private-sector...

Advisory Groups

How We're Funded

The work of the FAF, the FASB, and the GASB is funded by a combination of accounting support fees and publications and subscriptions income.

![]()

About Us

Financial reporting is the language that communicates information about the financial condition and operational results of a company (public or private), not-for-profit organization, or state or local government. Accounting standards determine how those financial statements are prepared. The standards are known collectively as Generally Accepted Accounting Principles—or GAAP.

The Financial Accounting Foundation (FAF) is the independent, private-sector, not-for-profit organization based in Norwalk, Connecticut, responsible for the oversight, administration, financing, and appointment of the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) and the Governmental Accounting Standards Board (GASB).

The FASB establishes financial accounting and reporting standards for public and private companies and not-for-profit organizations.

The GASB establishes financial accounting and reporting standards for U.S. state and local governments.

The FASB and the GASB are responsible for ensuring that GAAP remains the high-quality benchmark of financial reporting so that investors, lenders, capital providers, and other users of financial statements have access to the information they need to make better-informed decisions.

Our Mission

The collective mission of the FASB, the GASB, and the FAF is to establish and improve financial accounting and reporting standards so they provide useful information to investors and other users of financial reports and to educate stakeholders on how to most effectively understand and implement those standards.

The FASB, the GASB, the FAF Trustees, and the FAF management contribute to the collective mission according to each one’s specific role:

- The FASB and the GASB are charged with setting the highest-quality standards through a process that is robust, comprehensive, and inclusive.

- The FAF management is responsible for providing strategic counsel and services that support the work of the standard-setting Boards.

- The FAF Trustees are responsible for providing oversight and promoting an independent and effective standard-setting process.

Better standards.

Better-informed decisions.

Companies, not-for-profit organizations, and governments use accounting standards as a foundation for providing users of financial statements with relevant information. That information helps investors, lenders, citizens, and others make important decisions about whether to provide capital, lend or donate money, or whether or not to support a voter referendum.

It stands to reason, then, that better accounting standards help financial statement users make better-informed decisions.

The pursuit of better standards informs everything we do. The Financial Accounting Foundation (FAF) and its standard-setting Boards—the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) and the Governmental Accounting Standards Board (GASB)—are committed to fostering standards that result in information that is relevant, representationally faithful, and reflective of the financial condition of an organization or government.

What follows in these pages is a snapshot of how we fulfilled this objective in 2016. For the FASB, it meant issuing standards that give investors better information about an institution’s expected credit losses and lease obligations. For the GASB, it meant educating stakeholders about standards that enhance transparency around retirement obligations and developing an improved financial reporting model. And for the FAF, it meant supporting the Boards in these efforts while ensuring they follow a robust, inclusive due process.

Investors and citizens trust financial statements that follow Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP). Through our work, we aim to continue to earn that trust through standards that help all our stakeholders make better-informed decisions.

Message from the FAF Chairman and FAF President and CEO

Legendary football coach Vince Lombardi once said, “the achievements of an organization are the results of the combined effort of each individual.” That’s true on many levels for the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB), the Governmental Accounting Standards Board (GASB), and the Financial Accounting Foundation (FAF). Together, we work toward one goal: setting the highest-quality standards through a process that is robust, comprehensive, and inclusive.

While the FASB and the GASB set the standards that constitute Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP), the FAF works to provide a solid foundation for their success. For the FAF Trustees, that means ensuring the Boards follow a thoughtful, robust, and transparent process that considers a wide range of stakeholder views. For the FAF management team, it means providing strategic counsel and support to the Boards and our Trustees.

The eighteen FAF Trustees work with the FASB and the GASB to ensure that the process of setting GAAP standards is sound, and that the Boards follow it with discipline. We took several steps in 2016 to make our work in this area even more effective.

For example, in 2012 the Trustees established the Private Company Council (PCC) to serve as the primary advisory body to the FASB on private company matters. At that time, we assigned a group of Trustees to serve on a special Private Company Review Committee (PCRC). The PCRC’s mission was to oversee and hold the FASB and PCC accountable for ensuring private company perspectives were appropriately considered in the FASB’s standard-setting process.

Our three-year review of the role and effectiveness of the PCC (conducted in 2015) concluded that the PCC was meeting its objectives, so in 2016 the Trustees took steps to transition the PCRC’s oversight role to our existing Standard-Setting Process Oversight Committee effective January 1, 2017. To maintain continuity, members of the PCRC were appointed to the Oversight Committee, whose processes were enhanced to ensure the same level of oversight and attention would be given to private company perspectives during the standard-setting process.

One of the most important responsibilities of the Trustees is to appoint the right people to serve as the stewards of GAAP—people who bring to their roles diverse perspectives, extensive professional expertise, and a clear commitment to our mission.

In 2016, we considered hundreds of candidates for seats on both standard-setting Boards, as well as the Financial Accounting Standards Advisory Council (FASAC), the Governmental Accounting Standards Advisory Council (GASAC), the PCC, and our own FAF Board of Trustees. Through nationwide searches, we identified and appointed individuals with deep professional experience in various capital market roles.

Another priority of the FAF is to communicate the importance of setting standards that provide investors, credit providers, and other financial statement users with neutral, objective information that helps them efficiently and effectively make capital allocation decisions. For this reason, our office in Washington, DC regularly interacts with elected and appointed officials, including members of Congress and regulators.

In 2016, as in prior years, the Trustees visited these stakeholders to keep them informed of our activities and to explain why the work of our Boards benefits the U.S. capital markets and citizens. These visits also gave us the opportunity to learn what’s on the minds of elected representatives in Congress—and their constituents—as well as regulators, and to respond to their questions or concerns.

Finally, we made major progress on a multi-year information technology (IT) transformation project to implement the technology tools our standard-setting Boards need to carry out their responsibilities more effectively and efficiently. As part of this technology upgrade, we launched a more collaborative, secure online platform for the FASB and the GASB to develop proposed standards and other important documents.

We also started to build a customer relationship management (CRM) platform that will help the FASB and the GASB engage more systematically with their stakeholders. It will also enable the Boards to better organize, analyze, and understand input—especially comment letters—received from stakeholders. As of this writing, the CRM platform is near completion. We expect to fully realize its benefits later in 2017.

The FAF strives to create an environment that allows the FASB and the GASB to do their best work, while ensuring that the Boards engage with a broad range of stakeholders as part of the standard-setting process. We look forward to continuing to collaborate in these areas through 2017 and beyond.

On behalf of the FAF, thank you for your interest and involvement in our work.

Sincerely,

Charles H. Noski

Chairman

Teresa S. Polley

President and CEO

FAF Board of Trustees

Officers

Charles H. Noski

Chairman

Gary H. Bruebaker

Vice Chairman

Ann Marie Petach

Secretary and Treasurer

Teresa S. Polley

President and

Chief Executive Officer

Mary P. Crotty

Chief Operating Officer

John W. Auchincloss

Vice President, General

Counsel and Assistant

Secretary

Trustee Committees

Executive

Charles H. Noski, Chairman

Gary H. Bruebaker,

Vice Chairman

Charles S. Cox

Myra R. Drucker

Nancy K. Kopp

Ann M. Spruill

Terry D. Warfield

Appointments

Ann M. Spruill, Chair

Charles M. Allen

Christine M. Cumming

Anthony J. Dowd

Myra R. Drucker

T. Eloise Foster

Kenneth B. Robinson

Diane M. Rubin

Audit and Finance

Charles S. Cox, Chair

Charles M. Allen

Gary H. Bruebaker

Susan J. Carter

Christine M. Cumming

Ann Marie Petach

Kenneth B. Robinson

Compensation

Myra R. Drucker, Chair

Gary H. Bruebaker

Susan J. Carter

Charles S. Cox

Eugene Flood, Jr.

Ann Marie Petach

Ann M. Spruill

Standard-Setting

Process Oversight

Nancy K. Kopp, Co-Chair

Terry D. Warfield, Co-Chair

Anthony J. Dowd

John C. Dugan

Eugene Flood, Jr.

T. Eloise Foster

Diane M. Rubin

John B. Veihmeyer

Right, pictured from left to right:

Anthony J. Dowd

President and Chief Executive Officer

Fairfield Maxwell, LTD.

Nancy K. Kopp

Treasurer

State of Maryland

Christine M. Cumming

Retired First Vice President and Chief Operating Officer

Federal Reserve Bank

of New York

Charles M. Allen

Retired Partner and Past Chief Executive Officer

Crowe Horwath LLP

T. Eloise Foster

Chair

Maryland Supplemental Retirement Plans

Diane M. Rubin

Retired Audit Partner and Quality Control Partner

Novogradac & Company LLP

Left, pictured from left to right:

Susan J. Carter

Board Member

BlackRock Equity/Liquidity

Mutual Fund Board,

Pacific Pension and

Investment Institute

John C. Dugan

Partner

Covington & Burling LLP

Charles H. Noski

Chairman

FAF Board of Trustees

Retired Vice Chairman

Bank of America Corporation

Terry D. Warfield

PwC Professor in Accounting and Chair, Department of Accounting and Information Systems

University of Wisconsin, Madison

Right, pictured from left to right:

Gary H. Bruebaker

Vice Chairman

FAF Board of Trustees

Chief Investment Officer

Washington State

Investment Board

Kenneth B. Robinson

Senior Vice President

Exelon Corporation

Myra R. Drucker

Independent Director

Grantham, Mayo, Van Otterloo & Co. LLC

Ann Marie Petach

Secretary and Treasurer

FAF Board of Trustees

Board Member

BlackRock Institutional

Trust Company

John B. Veihmeyer

Chairman

KPMG International

Left, pictured from left to right:

Teresa S. Polley

President and Chief Executive Officer

Financial Accounting Foundation

Ann M. Spruill

Partner (Retired)

GMO & Co. LLC

Charles S. Cox

City Manager

City of Farmers Branch, Texas

Eugene Flood, Jr.

Board Member

Janus Capital Group Inc.

Welcome

During the past year, the FAF Board of Trustees welcomed Susan J. Carter, Anthony J. Dowd, and T. Eloise Foster.

Joined January 1, 2017

Susan J. Carter

Board Member

BlackRock Equity/Liquidity Mutual Fund Board, Pacific Pension and Investment Institute

Anthony J. Dowd

President and Chief Executive Officer

Fairfield Maxwell, LTD.

T. Eloise Foster

Chair

Maryland Supplemental Retirement Plans

Thank You

During the past year, Paul G. Camell, W. Daniel Ebersole, and Michelle R. Seitz concluded terms on the FAF Board of Trustees. On behalf of the entire organization, we thank them for their outstanding service.

Completed service on December 31, 2016

Paul G. Camell

Retired Executive Vice President and Chief Accounting Officer

CDM Smith Inc.

W. Daniel Ebersole

(FAF Vice Chairman)

Retired State Treasurer

State of Georgia

Michelle R. Seitz

Head of William Blair Investment Management

William Blair Investment

Messages from the

Message from the FASB Chairman

The FASB is entrusted with an important responsibility: developing accounting standards that neutrally reflect information that is relevant to investors and other financial statement users. With that responsibility comes the challenge of balancing competing interests of diverse capital market stakeholders, including investors.

In 2016, I’m pleased to report that the FASB delivered on that mission in many ways, including:

- Completing major new standards that better reflect the economics of leasing transactions and expected credit losses

- Reducing cost and complexity in the system by ensuring that preparers understand and consistently apply our standards—and that the information the standards provide is truly relevant to investors, and

- Ensuring that we serve all our stakeholders.

The leases standard we issued in February moves formerly off-balance sheet leasing activities onto the balance sheet. It addresses an area that investors told us needed to be improved, consistent with the findings of a 2005 Securities and Exchange Commission study on off-balance sheet reporting.

Issued in June, the new credit losses standard will result in more timely reporting of expected losses based on more forward-looking information—and will require enhanced transparency around the extent of those losses. The improved standard, years in development, was deeply informed by many hours of outreach with thousands of stakeholders around the world.

Other key standards issued in 2016 improved the recognition and measurement of financial instruments, financial reporting for not-for-profit organizations, and financial statements of employee benefit plans.

Our work doesn’t end when we issue a standard. In fact, that standard must come to life through robust education and training so that preparers understand it and apply it consistently. To that end, in 2016, we also focused on educating stakeholders about major standards prior to their effective dates—and simplifying other standards to reduce cost and complexity.

For example, we devoted considerable resources to monitoring the implementation of the upcoming revenue recognition standard through our Revenue Recognition Transition Resource Group (TRG). Based on feedback from the TRG, we clarified aspects of the revenue recognition guidance while making it more cost effective to implement.

We also created a Credit Losses TRG, which was informed by lessons learned from the Revenue Recognition group. Unlike its predecessor, the Credit Losses TRG met and provided feedback before the final standard was issued. This allowed us to address potential issues up front. While the FASB decided it was not necessary to create a leases TRG, our staff is closely monitoring questions that may arise around implementation of that standard.

To set effective standards, we also must make sure we’re addressing the right problems—and that means listening carefully to our stakeholders. In August, we issued an Invitation to Comment to solicit views on what we should tackle next—including potential projects on liabilities and equity, pensions, intangible assets, and financial performance reporting. Input was mixed, with some stakeholders observing that we should slow down on adding new projects until new standards have been successfully implemented. As one CPA wrote to us: “Take a vacation.”

We hear you. In 2017 our focus will be completing in-flight projects on hedging, long-term contracts issued by insurance companies, and redeliberating all aspects of our Disclosure Framework, anticipated for completion in 2018. We also will devote more resources to completing our Conceptual Framework, which will help future Board members arrive at conclusions that are more consistent so that standards are less complex. And, based on what you told us in the Invitation to Comment, the Board will vote on what its next agenda priorities should be.

We come to work every day with one big question on our minds: How can we serve all stakeholders better as we work to improve financial reporting? This is part of what I call the “cultural evolution” among all our members. It includes a shared understanding of the differences between public and nonpublic companies and not-for-profit organizations, and when those differences do—or do not—justify accounting alternatives. Our work with the Private Company Council is part of that effort.

It also drove our recent review of the efficiency of all our advisory groups. Based on that review, we refined the objectives of the Investor Advisory Committee and Small Business Advisory Committee to make their input even more meaningful. I look forward to working with these and all our advisory groups in 2017.

Thank you for continuing to share your views with the Board. Your input makes it possible for us to set standards that produce more relevant, useful information for the benefit of investors and all capital market participants.

Sincerely,

Russell G. Golden

Chairman

Members of the FASB

- Russell G. Golden

Chairman - James L. Kroeker

Vice Chairman - Christine Ann Botosan

Board Member - Harold L. Monk, Jr.

Board Member

- R. Harold Schroeder

Board Member - Marc A. Siegel

Board Member - Lawrence W. Smith

Board Member - Susan M. Cosper

Technical Director

2016 FASB Highlights

- Recognition and Measurement of Financial Assets and Financial Liabilities

- Leases

- Improvements to Employee Share-Based Payment Accounting

- Measurement of Credit Losses on Financial Instruments

- Presentation of Financial Statements of Not-for-Profit Entities

- Consolidation: Interests Held through Related Parties That Are under Common Control

- Narrow-Scope Improvements to Revenue Recognition Guidance:

- Principal versus Agent Considerations (Reporting Revenue Gross versus Net)

- Identifying Performance Obligations and Licensing

- Narrow-Scope Improvements and Practical Expedients

- Technical Corrections and Improvements

- Emerging Issues Task Force Consensuses:

- Liabilities—Extinguishments of Liabilities: Recognition of Breakage for Certain Prepaid Stored-Value Products

- Derivatives and Hedging: Effect of Derivative Contract Novations on Existing Hedge Accounting Relationships

- Derivatives and Hedging: Contingent Put and Call Options in Debt Instruments

- Statement of Cash Flows: Classification of Certain Cash Receipts and Cash Payments

- Statement of Cash Flows: Restricted Cash

- Private Company Council Consensus:

- Intangibles—Goodwill and Other, Business Combinations, Consolidation, Derivatives and Hedging: Effective Date and Transition Guidance

- Simplification:

- Simplifying the Transition to the Equity Method of Accounting

- Income Taxes: Intra-Entity Transfers of Assets Other Than Inventory

Welcome

During the past year, the FASB welcomed Christine Ann Botosan and Harold L. Monk, Jr.

Joined July 1, 2016

Christine Ann Botosan

Prior to joining the FASB, Ms. Botosan served as a professor of accounting at the David Eccles School of Business at the University of Utah.

Joined January 1, 2017

Harold L. Monk, Jr.

Prior to joining the FASB, Mr. Monk served as a partner with Carr, Riggs & Ingram, LLC.

Thank You

Last year, Thomas J. Linsmeier and Daryl E. Buck concluded terms on the FASB. On behalf of the entire organization, we thank them for their outstanding service.

Thomas J. Linsmeier

Served on the FASB

from July 1, 2006

to June 30, 2016.

Daryl E. Buck

Served on the FASB

from February 28, 2011

to December 31, 2016.

Messages from the

Message from the GASB Chairman

The work we do at the GASB leads to information that you can understand, trust, and put to work. By put to work, I mean that financial statements prepared using our standards can provide key information that will help you answer many foundational questions.

Questions like:

- Should I invest in this bond?

- Is this community right for our family?

- Is this school district on solid financial ground?

While financial reporting may not provide all the information needed to answer these questions—and, in some cases, may be just one of several resources that will be used—it does provide valuable information that places the reader in a position to be able to make better-informed decisions.

The GASB made significant progress in 2016 on improving accounting and financial reporting standards for the more than 90,000 state and local governments in the United States. We also focused on educating stakeholders about the impact of our work.

Postemployment Benefits

We continued our stakeholder outreach and education on pensions and other postemployment benefits (OPEB), which includes retiree healthcare.

Together, these standards are meant to provide a clear, consistent, and comprehensive picture of what governments have promised—and how much it will cost taxpayers and other resource providers to honor those promises.

To help put it in perspective, more than 14 million of the 120+ million full-time employees in the United States work in state and local government. These numbers don’t reflect the millions more who have retired from careers in government.

In 2015, governments paid more than $132 billion into the pension plans that hold $3.8 trillion in assets for these workers. These plans generated nearly $169 billion in investment income in 2015 with those assets, and they paid out $266 billion in benefits over the year. When the numbers have this many digits and the stakes are the futures of millions of current and retired workers, it’s important that everyone has access to the right information.

Our work helps investors, citizens, and others gain greater insight into governments’ pension and OPEB promises. But it also helps governments track whether the promises they’ve made are in-line with money they’ve set aside to honor them—or if adjustments may be needed.

These standards mean significant changes for how governments prepare financial statements, how auditors attest to those statements, and how investors, residents, and others analyze them. We know it’s a lot to digest so we’re doing several things to help stakeholders prepare.

Last year, this included:

- Offering 100+ presentations across the country

- Having staff available to answer questions by telephone

- Hosting and participating in webinars

- Conducting media and stakeholder outreach, and

- Developing guides to provide answers to key implementation questions.

Because the OPEB standards will become effective for OPEB plans this summer and for government employers next year, we’ll continue these kinds of efforts to help promote as smooth a transition as possible to reporting under the new requirements.

The Blueprint

We’re also taking a fresh look at the fundamental blueprint for financial reports—the financial reporting model. After two years of research, input from hundreds of financial statement users, preparers, and auditors, and more than a year of work at the Board table, the GASB issued a document for comment just before year-end.

Ultimately, we want to make sure the right information is presented in the financial reports—and that it’s being presented in the best way for the people who rely on it.

This project is the first of three related efforts that will let the GASB take a comprehensive look at financial reporting over the coming years—and to make targeted improvements. The next project addresses revenue and expense recognition to make those standards adapt to an ever-changing environment. Finally, the GASB staff currently is undertaking a comprehensive research effort to assess the effectiveness of note disclosures.

We’ve staggered the timing of “The Big Three” to allow us to work on them in unison and issue them consecutively—so the information is available as quickly as possible.

Final Thoughts

In 2017, the GASB is continuing to build on the progress we’ve made to make sure stakeholders have the information they need. If you have ideas about how the Board can do that better, I’d be eager to hear from you.

Stakeholder feedback drives our work. In 2016, in one way or another, thousands of you reached out to share your views. That’s very gratifying and we appreciate your engagement.

To everyone who took the time to share ideas with us in 2016, I extend the GASB’s sincere thanks—and encourage you to continue to collaborate with us over the coming year. For those who have not taken this opportunity in the past, now is the perfect time to have your voice be heard.

Sincerely,

David A. Vaudt

Chairman

Members of the GASB

- David A. Vaudt

Chairman - Jan I. Sylvis

Vice Chairman - James E. Brown

Board Member - Brian W. Caputo

Board Member

- Michael H. Granof

Board Member - Jeffrey J. Previdi

Board Member - David E. Sundstrom

Board Member - David R. Bean

Director of Research and Technical Activities

2016 GASB Highlights

Final Statements

- Certain Asset Retirement Obligations

- Pension Issues

- Irrevocable Split-Interest Agreements

- Blending Requirements for Certain Component Units

- Implementation Guidance Update—2016

Proposals

- Exposure Drafts

- Omnibus

- Certain Debt Extinguishment Issues

- Leases

- Invitation to Comment

- Financial Reporting Model Improvements— Governmental Funds

- Exposure Draft, Implementation Guides

- Implementation Guidance Update

- Financial Reporting for Postemployment Benefit Plans Other Than Pension Plans

Welcome

Last year, the GASB welcomed Jeffrey J. Previdi to the Board.

Joined July 1, 2016

Jeffrey J. Previdi

Prior to joining the GASB, Mr. Previdi served in a variety of roles for more than two decades at Standard & Poor’s Ratings Services.

Thank You

Last year, William W. Fish concluded his term on the GASB. On behalf of the organization, we thank him for his outstanding service.

William W. Fish

Served on the GASB

from February 1, 2012

to June 30, 2016.

Messages from the

Better Standards: Credit Losses

Banks and other lenders are in the business of taking measured credit risk. With this risk comes some expectation that not every loan will be repaid.

Traditionally, Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) has required an “incurred loss” accounting model for recognizing such losses, meaning that the loss from a specific loan isn’t recognized until it is probable a loss has been incurred. This model has been criticized for unduly delaying the recognition of reserves in an economic downturn.

The global financial crisis of 2007–2008 underscored this criticism.

During the run-up to the financial crisis, financial statement users recognized the rising credit risk. So, well before accounting rules permitted the recognition of those losses, investors began to compensate for known shortcomings in GAAP by making their own estimates of expected credit losses using forward-looking information and devaluing financial institutions. This common practice highlighted the fact that the information needs of users were not satisfied by GAAP.

Similarly, preparers expressed frustration during this period because they could not record credit losses that they were expecting simply because an accounting threshold of “probable” had not been met.

On June 16, 2016, the FASB issued a standard that will require more timely recording of credit losses on loans and other financial instruments held by all entities including financial institutions.

The new standard aligns the accounting with the economics associated with changes in credit risk by requiring lenders to immediately record the full amount of expected credit losses as loans are originated, thereby providing investors with management’s expectations of losses on a more timely basis.

The new standard will require management’s expectation of credit losses for financial assets to be based on historical experience and current conditions, as well as reasonable and supportable forecasts. It requires financial institutions to use forward-looking information to better inform their credit loss estimates, thus aligning the different stakeholders on the same path.

On June 16, 2016, the FASB issued a standard that will require more timely recording of credit losses on loans and other financial instruments held by all entities including financial institutions.

FASB Outreach on the credit losses standard

Meetings with

more than

200

users of

financial statements

![]()

![]()

More than

85

meetings and

workshops with

preparers

10+

roundtables with more

than 100 representatives

including users, preparers,

regulators, and auditors

![]()

![]()

25

fieldwork meetings with

preparers from industries

including banking

institutions of various sizes,

nonfinancial organizations,

and insurance companies

Better Standards: Leases

Leasing is integral to the modern economy. Each year, trillions of dollars’ worth of airplanes, buildings, cars, construction equipment, and other assets are leased for many obvious reasons: leasing is a means of gaining access to assets while reducing an organization’s exposure to the risks of full ownership.

However, investors and others have criticized the current operating lease accounting model for sometimes failing to provide them with a faithful representation of leasing transactions. The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission echoed these concerns in a 2005 staff report on off-balance sheet activities that recommended changes to the existing lease accounting requirements.

To address these concerns, in February 2016, the FASB issued a new standard intended to improve transparency around lease obligations. The standard will require organizations that lease assets—referred to as “lessees”—to recognize on the balance sheet the assets and liabilities for the rights and obligations created by those leases.

Under the new guidance, a lessee will be required to recognize assets and liabilities for all leases with lease terms of more than 12 months. Consistent with current Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP), the recognition, measurement, and presentation of expenses and cash flows arising from a lease by a lessee primarily will depend on its classification as a finance or operating lease.

However, unlike current GAAP—which requires only capital leases to be recognized on the balance sheet—the new standard will require both types of leases to be recognized on the balance sheet.

The standard also will require enhanced disclosures to help investors and other financial statement users better understand the amount, timing, and uncertainty of cash flows arising from leases.

The standard will require organizations that lease assets—referred to as “lessees”—to recognize on the balance sheet the assets and liabilities for the rights and obligations created by those leases.

FASB Outreach on the leases standard

More than

200

meetings with

preparers and users

(which included

private companies

and not-for-profit

organizations)

![]()

15

public roundtables,

with more than

180

representatives and

organizations, and

2

roundtables that were

focused specifically

on private companies

and not-for-profits

15

preparer workshops

attended by

representatives

from more than

90

organizations

![]()

![]()

14

fieldwork

meetings

with preparers

Both the FASB and the

International Accounting

Standards Board (IASB)

met with more than

500

users of financial

statements

![]()

Better Standards: Postemployment Benefits

The GASB’s new generation of standards for pensions and retiree health care benefits are designed to provide a more complete picture of the benefits governments have promised to provide—including clear information on how much they cost.

The standards now feature an independent accounting approach—and separate how governments account for these benefits from how they fund them.

Fundamental changes like these introduce new information—that means stakeholders are going to have questions and need support as they transition to the new requirements. To help preparers, auditors, and financial statement users during the transition, we’re focused on answering the questions they have and providing the educational opportunities they need.

In 2016, we engaged with stakeholders in all 50 states—in person, on the telephone, and by webcast. Our outreach included more than 100 targeted, specifically tailored presentations to all types of stakeholder groups ranging in size from a few dozen to several thousand. In these sessions, we walked stakeholders step-by-step through how the new requirements work—and answered their questions as they arose.

Through our technical inquiry hotline, we answered more than 500 specific real-life questions on pensions and other postemployment benefits (OPEB). Some of these wrapped up in only ten minutes while others required many hours with several follow-up calls.

As we meet with stakeholders to talk about their issues, it often becomes clear that certain questions should be addressed more broadly. GASB Implementation Guides provide answers to just these kinds of broad-application questions. We’ve already issued guides on common pensions questions and are finalizing guides on OPEB this year.

The GASB works hard to make sure stakeholders have the information they need to put our standards to work. If you have questions or need clarification on postemployment benefit issues—or any other area of governmental accounting—we’d be very pleased to hear from you.

The standards now feature an independent accounting approach—and separate how governments account for these benefits from how they fund them.

GASB Outreach on the postemployment benefits standards

Outreach

to all

50

states

![]()

![]()

More than

100

stakeholder

presentations

across the country

Answered

more than

500

case-specific

stakeholder

questions

![]()

![]()

Provided

Implementation

Guides with

Q&As

addressing

many key issues

Better Standards: Financial Reporting Model

The financial reporting model is the fundamental blueprint for governmental financial reports. Because GASB research indicates that the model is working as intended for the most part, our work doesn’t start with a clean sheet of paper. Instead, we’re focusing on targeted areas of improvement.

The GASB began this effort by conducting extensive outreach with stakeholders. We held 10 roundtable discussions across the country to get a handle on what stakeholders believed was working with the model and what issues needed further consideration. As it turns out, the 144 of you who took part had a lot to say. While we did gain the rich variety of perspectives that we were hoping for, one message came through loud and clear: don’t throw the baby out with the bath water.

Your input informed the crafting of surveys, which brought us expanded feedback from hundreds more stakeholders—including 265 financial statement preparers, 164 auditors, and 184 users.

What the GASB learned from the survey results set the stage for nearly 150 deeper-dive interviews with a cross section of stakeholders that provided additional texture—and more specifics into what kind of targeted improvements they believed would improve the model.

With all this input as our guide, the Board formally added the project to the agenda in September 2015. Then, after more than a year of discussion at the Board table, we ultimately issued a draft document, and we asked for still more feedback from you.

In the past few months, more than 100 of you or organizations that represent you shared your views with us in writing—and several dozen more offered perspectives during a series of public hearings and user forums that we held across the country.

This degree of stakeholder involvement is the foundation of high-quality standard setting. Your feedback and ideas will be critical factors in shaping the future of this project and will influence the path that the Board chooses to improving the financial reporting model.

Because GASB research indicates that the model is working as intended for the most part, our work doesn’t start with a clean sheet of paper. Instead, we’re focusing on targeted areas of improvement.

GASB Outreach on the financial reporting model

10

roundtables with

144

participants

![]()

Research included

hundreds of survey

participants:

Preparers:

265

Auditors:

164

Users:

184

Almost

150

deeper-dive

interviews

![]()

![]()

More than

100

comment letters

to the Invitation

to Comment

Five public hearings

and three user forums

held in spring 2017

with almost

100

participants

![]()

Advisory Groups

Advisory and other groups provide critical input to the FASB and the GASB. Complete membership rosters for each group are available by clicking on the group's icon below.

FASB ADVISORY GROUPS

Financial Accounting Standards Advisory Council

Advises the FASB on issues related to projects on the Board’s agenda, possible new agenda items, project priorities, procedural matters that may require the attention of the FASB, and other matters as requested by the chairman of the FASB. FASAC meetings provide the Board with an opportunity to obtain and discuss the views of a very diverse group of individuals from varied business and professional backgrounds.

Investor Advisory Committee

Provides advice, from the investors’ perspective, on current and potential FASB agenda projects.

Not-for-Profit Advisory Committee

Provides advice on existing guidance, current and proposed technical agenda projects, and longer-term issues related to the not-for-profit sector.

Small Business Advisory Committee

Provides advice on FASB projects related to the operationality and the anticipated costs, complexities, and benefits of potential solutions principally from a small public company perspective.

OTHER KEY FASB GROUPS

Emerging Issues Task Force

The mission of the EITF is to assist the FASB in improving financial reporting through the timely identification, discussion, and resolution of financial accounting issues within the framework of the FASB Accounting Standards Codification®.

Private Company Council

The PCC is the primary advisory body to the FASB on private company matters. The PCC uses the Private Company Decision-Making Framework to advise the FASB on the appropriate accounting treatment for private companies for items under active consideration on the FASB’s technical agenda. The PCC also advises the FASB on possible alternatives within GAAP to address the needs of users of private company financial statements. Any proposed changes to GAAP are subject to endorsement by the FASB.

GASB ADVISORY GROUP

Governmental Accounting Standards Advisory Council

Consults with the GASB on technical issues on the Board’s agenda, project priorities, matters likely to require the attention of the GASB, selection and organization of task forces, and such other matters as may be requested by the GASB or its chairman. GASAC meetings provide the Board with an opportunity to obtain and discuss views with a broad representation of preparers, attestors, and users of financial information.

Financial Accounting Standards Advisory Council

![]()

Advises the FASB on issues related to projects on the Board’s agenda, possible new agenda items, project priorities, procedural matters that may require the attention of the FASB, and other matters as requested by the chairman of the FASB. FASAC meetings provide the Board with an opportunity to obtain and discuss the views of a very diverse group of individuals from varied business and professional backgrounds.

FASAC Chair

Andrew G. McMaster, Jr.

FASAC Executive Director

Alicia A. Posta

Members

Kimber Bascom

Partner

KPMG LLP

Stuart Birdt

Investment Officer

Interlaken Management, LLC

R. Scott Blackley

Chief Financial Officer

Capital One

Gary Buesser

Director

Lazard Asset Management

Susan M. Callahan*

Director, Americas Accounting and Global Accounting Policy

Ford Motor Company

Colleen K. Conrad

Executive Vice President and Chief Operating Officer

National Association of State Boards of Accountancy

Mr. Richard E. Forrestel, Jr.*

Treasurer

Cold Spring Construction Company, Inc.

Marie T. Gallagher

Senior Vice President and Controller

PepsiCo, Inc.

Sydney Garmong

Partner

Crowe Horwath LLP

Sameer Gokhale

Senior Director, Investor Relations

Fifth Third Bancorp

Jeffrey Hales

Catherine W. and Edwin A. Wahlen, Jr.

Professor of Accounting

Georgia Institute of Technology

Xihao Hu

Executive Vice President, Finance and

Head of Accounting, Tax, Planning and Finance Shared Services

TD Bank

Richard R. Jones

Partner—Director of Accounting

EY

Mark LaMonte

Managing Director

Moody’s Investors Service

Timothy J. LaSpaluto

Chief Financial Officer

AICPA

Dan Mahoney

Director of Research

CFRA

Maya McReynolds

Vice President Finance and Chief Accounting Officer

Dell Inc.

Daniel S. Meader

Principal

Trinity Private Equity Group LP

Sean C. Miller

Vice President—Technical Accounting

Sony Pictures Entertainment

Bob Mims*

Former Controller/Director of Investments

Ducks Unlimited, Inc.

John G. Morriss

Senior Vice President, Head of Fixed Income Research, Investment Management

Lincoln Financial Group

Gregg L. Nelson

Vice President and Chief Accounting Officer

IBM Corporation

Douglas R. Oare

Managing Director

BlackRock, Inc.

Thomas Omberg

National Leader, Financial Accounting and Reporting Services

Deloitte & Touche LLP

Cathy Shakespeare

Associate Professor of Accounting

University of Michigan

Sherry M. Smith

Board of Directors

Deere & Company, Tuesday Morning Corporation, and

Realogy Holdings Corporation

Lee Sotos

Senior Analyst

Fidelity Worldwide Investment

Ted T. Timmermans

Vice President, Controller and Chief Accounting Officer

The Williams Companies, Inc.

Sharon A. Virag

Vice President, Controller, and Chief Accounting Officer

Aetna

Joan E. Waggoner

Partner in Professional Standards

Plante Moran PLLC

Thomas W. White*

Partner

WilmerHale LLP

Jeffrey Wilks

Director and EY Professor

School of Accountancy

Brigham Young University

Randall Woods

Principal/Head of Investing for Pension Funds

RJW Financial Services

Louis Zahorak*

Investment Director

CalPers

*New members in 2017

Completed Service in 2016

Linda L. Griggs

Partner

Morgan, Lewis and Bockius LLP

Michael (Mick) G. Homan

Vice President, Finance and Accounting—Corporate Accounting

Procter & Gamble (P&G) Company

Marsha L. Hunt

Vice President—Corporate Controller

Cummins Inc.

Catherine E. Mickle

Chief Financial Officer

American Cancer Society

Other Advisory Groups

Investor Advisory Committee

![]()

Provides advice, from the investors’ perspective, on current and potential FASB agenda projects.

IAC Chair

Susan M. Cosper

Technical Director

Financial Accounting Standards Board

Members

Frederick Cannon

Global Director of Research, Chief Equity Strategist,

and Executive Vice President

Keefe, Bruyette, & Woods, Inc.

Todd Castagno*

Executive Director and Equity Research Analyst

Morgan Stanley

Trevor S. Harris*

Arthur J. Samberg Professor of Professional Practice, Accounting

Columbia Business School

Katherine Hensel*

Private Investor

Shripad Joshi*

Senior Director

S&P Global Ratings

Jill Lehman

Head of Healthcare and TMT Research

CFRA

Matthew Schechter

Head, Forensic Accounting

Balyasny Asset Management LP

Kevin W. Shea

Chief Executive Officer

Disciplined Alpha LLC

David Trainer

Chief Executive Officer

New Constructs LLC

Steven Y. Yang*

Equity Investment Analyst

Schroders Investment Management

*New members in 2017

Completed Service in 2016

Wallace Enman

Senior Accounting Analyst

Moody’s Investors Service

Other Advisory Groups

Not-for-Profit Advisory Committee

![]()

Provides advice on existing guidance, current and proposed technical agenda projects, and longer-term issues related to the not-for-profit sector.

Committee Chair

Jeffrey D. Mechanick

Assistant Director—Nonpublic Entities

Financial Accounting Standards Board

Members

Alice Antonelli

Director, Advisory Services

Nonprofit Finance Fund

Cathy Clarke

Chief Assurance Officer

Clifton Larson Allen, LLP

Mary Connick*

Senior Vice President, Finance and Corporate Controller

Dignity Health

Jim Croft

Principal

JWC Consulting Group

Former Executive Vice President and Chief Financial Officer

The Field Museum of Natural History

Harvey Dale

University Professor of Philanthropy and the Law

Director, National Center of Philanthropy and the Law

New York University School of Law

Michael Forster

Chief Financial Officer

Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars

Kelly Frank*

Partner

Not-for-Profit and Education Industry Practice Leader

CohnReznick LLP

David Gagnon*

Partner, Audit

National Industry Leader, Higher Education and Other Not-for-Profits

KPMG LLP

Deborah Gillespie

Vice President, Finance and Administration

and Secretary/Treasurer

The Joyce Foundation

John Kroll

Associate Vice President for Finance and Acting Chief Financial Officer

The University of Chicago

Bob Mims

Former Controller/Director of Investments

Ducks Unlimited, Inc.

Carolyn Mollen*

Vice President and Chief Financial Officer

Independent Sector

Dennis Morrone*

Partner-in-Charge, National NFP Audit Practice

Grant Thornton LLP

Norman C. Mosrie

Partner

Dixon Hughes Goodman

Linda M. Parsons

Associate Professor of Accounting

Culverhouse School of Accountancy

University of Alabama

Andrew Prather

Shareholder

Clark Nuber P.S.

Amy B. Robinson

Vice President, Chief Financial Officer and Chief Administrative Officer

The Kresge Foundation

Bennett M. Weiner

Chief Operating Officer

Better Business Bureau Wise Giving Alliance

*New members in 2017

Participating Observers

Dena Markowitz

Chief, Division of Investigations

Pennsylvania Bureau of Corporations and Charitable Organizations

(representing National Association of State Charity Officials)

Christopher Cole

Senior Technical Manager and Not-For-Profit Expert Panel Staff Liaison

AICPA

Completed Service in 2016

Gordon T. Edwards

Chief Financial Officer

Marshfield Clinic Health System

Kenneth C. Euwema

Vice President and Controller

United Way Worldwide

Roger Goodman

Partner

The Yuba Group LLC

John Mattie

Partner-in-Charge, Higher Education

and Not-for-Profit Industry Practice

PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP

Cynthia A. Pierce

Partner-in-Charge, Higher Education

and Not-for-Profit Industry Practice

Crowe Horwath LLP

Other Advisory Groups

Small Business Advisory Committee

![]()

Provides advice on FASB projects related to the operationality and the anticipated costs, complexities, and benefits of potential solutions principally from a small public company perspective.

SBAC Chair

Alicia A. Posta

Assistant Director

Financial Accounting Standards Board

Members

Gary J. Bachman

Chief Operating Officer (former CFO)

Pzena Investment Management, Inc.

Tim Caffrey

President/Portfolio Manager

Ty View Capital

Rick Day

Partner, National Director of Accounting

RSM US LLP

John Exline

Chief Financial Officer

Clark Investment Group

David Gonzales

Accounting Analyst

Moody's Investor Service

Shannon Greene

Chief Executive Officer

Tandy Leather

David W. Hinshaw

Managing Partner, Professional Standards Group and SEC Practice

Dixon Hughes Goodman LLP (DHG)

Robert Hoffman

Chief Financial Officer

Innovus Pharmaceuticals, Inc.

Cortney Johnson

Chief Financial Officer

All Web Leads, Inc.

Greg Kowieski

Partner

Moss Adams LLP

Marshall Minoux

Underwriting Director/Construction Services

Travelers

Doug Reynolds

Partner, Accounting Principles Consulting Group

Grant Thornton

Robert B. Vogt

Partner, Professional Practice Group

EY

William Waller

Portfolio Manager/Managing Member

M3 Funds, LLC and M3F

John Zimmer

President

First Lake Advisors

Other Advisory Groups

Emerging Issues Task Force

![]()

The mission of the EITF is to assist the FASB in improving financial reporting through the timely identification, discussion, and resolution of financial accounting issues within the framework of the FASB Accounting Standards Codification®.

EITF Chair

Susan M. Cosper

Technical Director

Financial Accounting Standards Board

EITF Coordinator

Rob Moynihan

Practice Fellow

Financial Accounting Standards Board

Members

John M. Althoff

Partner

PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP

Paul A. Beswick

Partner

EY

James G. Campbell

Corporate Controller

Alphabet Inc.

Terri Z. Campbell

Senior Managing Director

Liberty Mutual Group Asset Management Inc.

Alexander M. Corl

Chief Financial Officer & Treasurer

The Lee Company

Bret Dooley

Managing Director and Director of Corporate Accounting Policies Group

Corporate Accounting Policies Group

JPMorgan Chase & Co

Carl Kampel

Director in Charge of Professional Standards

Ellin & Tucker, Chartered

Mark LaMonte

Vice President—Senior Credit Officer, Financial Institutions Group/ Accounting Specialist Group

Moody’s Investors Service

Robert B. Malhotra

Partner

KPMG LLP

Lawrence J. Salva

Senior Vice President, Chief Accounting Officer & Controller

Comcast Corporation

Mark Scoles

Partner-In-Charge, Accounting Principles

Grant Thornton LLP

Ashwinpaul C. (Tony) Sondhi

President

A.C. Sondhi & Associates, LLC

Robert Uhl

Partner

Deloitte & Touche LLP

Participating Observers

Wesley R. Bricker

Chief Accountant

U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission

(SEC Observer)

James A. Dolinar

Partner

Crowe Horwath LLP

(FinREC Observer)

Yan Zhang*

Partner

EisnerAmper LLP

(PCC Observer)

*New members in 2017

Completed Service in 2016

Mark A. Pollock

Practice Fellow

Financial Accounting Standards Board

Thomas J. Groskopf

Director and Owner

Barnes, Dennig & Co., LTD

(PCC Observer)

Other Advisory Groups

Private Company Council

![]()

The PCC is the primary advisory body to the FASB on private company matters. The PCC uses the Private Company Decision-Making Framework to advise the FASB on the appropriate accounting treatment for private companies for items under active consideration on the FASB’s technical agenda. The PCC also advises the FASB on possible alternatives within GAAP to address the needs of users of private company financial statements. Any proposed changes to GAAP are subject to endorsement by the FASB.

PCC Chair

Candace E. Wright

Director

Postlethwaite & Netterville

FASB Liaison

Harold L. Monk, Jr.

Member

Financial Accounting Standards Board

PCC Coordinator

Michael K. Cheng

Supervising Project Manager

Financial Accounting Standards Board

Members

Steven Brown

Credit Risk Manager and Senior Vice President

US Bank

Jeffery Bryan

Partner, Professional Standards Group

Dixon Hughes Goodman LLP

Timothy J. Curt

Managing Director and Partner

Warburg Pincus LLC

David J. Hirsch*

Vice President, Finance

Pritzker Group Private Capital

David S. Lomax

Assistant Vice President and Underwriting Officer

Liberty Mutual Insurance Company

Richard N. Reisig*

Shareholder and Technical Director, Attest Services

Anderson ZurMuehlen & Company, PC

Beth I. van Bladel*

Director

CFO for Hire LLC

Lawrence E. Weinstock

Vice President—Finance

Mana Products, Inc.

Yan Zhang*

Partner

EisnerAmper LLP

*New members in 2017

Completed Service in 2016

George W. Beckwith

Vice President and Chief Financial Officer

National Gypsum Company

Thomas J. Groskopf

Director and Owner

Barnes, Dennig & Co., LTD

Harold L. Monk, Jr.

Partner

Carr, Riggs & Ingram LLC

Carleton L. Olmanson

Managing Principal

GMB Mezzanine

Other Advisory Groups

Governmental Accounting Standards Advisory Council

![]()

Consults with the GASB on technical issues on the Board’s agenda, project priorities, matters likely to require the attention of the GASB, selection and organization of task forces, and such other matters as may be requested by the GASB or its chairman. GASAC meetings provide the Board with an opportunity to obtain and discuss views with a broad representation of preparers, attestors, and users of financial information.

GASAC Chair

Robert W. Scott

Director, Finance

City of Brookfield, Wisconsin

(Nominated by the Government Finance Officers Association)

GASAC Vice Chair

Jacqueline L. Reck

James E. Rooks and C. Ellis Rooks Distinguished Professor of Accounting

School of Accountancy

University of South Florida

(Nominated by the American Accounting Association)

Members

Benjamin Barnes

Secretary, Office of Policy and Management

State of Connecticut

(Nominated by the National Governors Association)

Alan D. Conroy*

Executive Director

Kansas Public Employees Retirement System

(Nominated by the Council of State Governments)

Wayne Gerhold

Principal

Law Offices of Wayne D. Gerhold

(Nominated by the National Association of Bond Lawyers)

Brian Green

Partner, Healthcare Audit and Reimbursement Services

Seim Johnson

(Nominated by the Healthcare Financial Management Association)

Demetria Hanna

Branch Chief, Economic Statistical Methods Division

U.S. Census Bureau

(Nominated by the U.S. Census Bureau)

Shirley D. Hughes

City Administrator

City of Liberty, South Carolina

(Nominated by the International City/County Management Association)

Stephen Klein

Chief Fiscal Officer, Legislative Joint Fiscal Office

State of Vermont

(Nominated by the National Conference of State Legislatures)

James Lanzarotta

Partner

Moss Adams

(Nominated by the AICPA)

Richard Larkin

Director, Municipal Credit Analysis

Stoever Glass & Company

(Nominated by the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association)

Gerard Lian

Senior Analyst, Fixed Income Team

Invesco

(Nominated by the Investment Company Institute)

David H. Lillard, Jr.

State Treasurer

State of Tennessee

(Nominated by the National Association of State Treasurers)

Lealan Miller

Director, Government Services

Eide Bailly

(Nominated by the Association of Government Accountants)

Sandra Moorman

Director, Controller, Accounting Department

Sacramento Municipal Utility District

(Nominated by the American Public Power Association)

B. Sue Osborn*

Mayor

City of Fenton, Michigan

(Nominated by the National League of Cities)

Mark Pepera

Chief Financial Officer

Brunswick City Schools, Ohio

(Nominated by the Association of School Business Officials International)

Robert M. Reardon

Senior Investment Officer

State Farm Insurance Company

(Nominated by the Insurance Industry Investors)

Tasha Repp

Business Assurance Partner, Tribal Services Group

Moss Adams

(Nominated by the Native American Finance Officers Association)

Phyllis Resnick*

Lead Economist and Deputy Director

Colorado Futures Center at Colorado State University

(Nominated by the Governmental Research Association)

Alan Skelton

State Accounting Officer

State of Georgia

(Nominated by the National Association of State Auditors, Comptrollers, and Treasurers)

Daniel Smith

Associate Professor and Program Director—MPA

School of Public Policy and Administration

University of Delaware

(Nominated by the Association for Budgeting and Financial Management)

Gilbert L. Southwell III

Vice President and Senior Municipal Analyst

Wells Capital Management

(Nominated by the National Federation of Municipal Analysts)

Larry Stafford*

Audit Services Manager

Clark County, Washington

(Nominated by the Association of Local Government Auditors)

Charles A. Tegen

Associate Vice President for Finance

Clemson University

(Nominated by the National Association of College and University Business Officers)

James R. Wells

Director, Governor's Finance Office

State of Nevada

(Nominated by the National Association of State Budget Officers)

Robert A. Wylie

Executive Director

South Dakota Retirement System

(Nominated by the National Association of State Retirement Administrators)

*New members in 2017

Official Observer

Robert Dacey

Chief Accountant

Representing the Comptroller General of the United States

Government Accountability Office

Completed Service in 2016

Perry James

Chief Financial Officer

City of Raleigh, North Carolina

Amanda Noble

Deputy City Auditor

City of Atlanta, Georgia

Joseph Stefko

President and Chief Executive Officer

Center for Governmental Research

Teri F. Wenck

Director, Public Finance Group

FitchRatings

Glen Whitley

County Judge

Tarrant County, Texas

Other Advisory Groups

How We’re Funded

The work of the FAF, the FASB, and the GASB is funded by a combination of accounting support fees and publications and subscriptions income.

WHAT ARE ACCOUNTING SUPPORT FEES?

Accounting support fees are collected from certain groups of capital market participants:

- For the FASB, accounting support fees are collected from public market equity issuers and investment company issuers (as provided by the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002).

- For the GASB, accounting support fees are collected from municipal bond broker dealers (as provided by the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act of 2010).

HOW DO WE DETERMINE THE ANNUAL SUPPORT FEE?

The laws that enacted the accounting support fees permit the FAF to recoup the Boards’ full annual budgeted recoverable expenses. Historically, the FAF has voluntarily funded a portion of the Boards’ recoverable expenses with available Reserve Funds.

First, the FAF creates its budget. The FAF then determines its voluntary calculated amount available from its Reserve Funds to offset a portion of its recoverable expenses, and only recoups accounting support fees on the balance of recoverable expenses.

Over the past four years, contributions from the Reserve Fund have offset a total of $73 million that otherwise would have been collected through accounting support fees.

![]()

For more information, visit our “How We’re Funded” page at www.accountingfoundation.org.

HOW DO WE DETERMINE THE VOLUNTARY RESERVE FUND CONTRIBUTION?

The FAF’s policy is to maintain a Reserve Fund that is equal to one year of budgeted operating expenses. Reserve Funds are principally funded by revenue from the FAF sales and licensing of copyrighted FASB- and GASB-related materials and income earned from FAF investments.

![]()

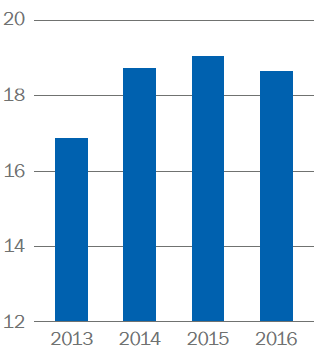

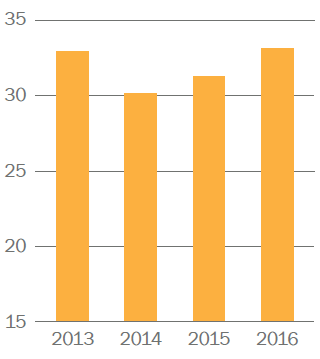

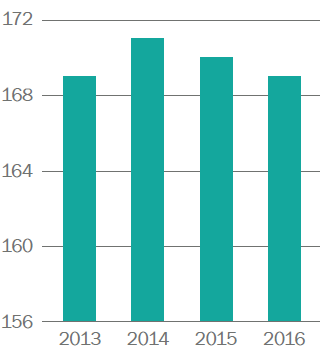

Key Financial Metrics 2013–2016

Contributions from Reserve Funds

($ millions)

Accounting Support Fees

($ millions)

Headcount

Management's Discussion and Analysis

2016 Summary

The mission of the Financial Accounting Foundation (FAF) and its standard-setting Boards, the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) and the Governmental Accounting Standards Board (GASB), is to establish and improve standards of financial accounting and reporting for public and private companies, not-for-profit organizations, and state and local governments. Collectively, these standards are known as Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP). Financial accounting and reporting standards help foster and protect investor confidence, facilitate the efficient operation of capital markets, and enable citizens to assess the stewardship of public resources by their state and local governments. The FAF, the FASB, and the GASB are committed to the development of high-quality financial accounting and reporting standards through an independent and open process that results in useful financial information, considers all stakeholder views, and ensures public accountability.

The FAF is responsible for the oversight, administration, financing, and appointment of the FASB and the GASB, and their respective advisory councils, the Financial Accounting Standards Advisory Council (FASAC), and the Governmental Accounting Standards Advisory Council (GASAC). The FAF obtains its funding from three sources:

- Accounting support fees that finance FASB operating and capital expenses pursuant to Section 109 of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 (Sarbanes-Oxley Act);

- Accounting support fees that finance GASB operating and capital expenses pursuant to Section 978 of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act of 2010 (Dodd-Frank Act); and

- Sales and licensing of copyrighted FASB and GASB materials.

The FAF’s net assets decreased by $4.9 million in 2016 as total program and support expenses exceeded total net operating revenues by $5.9 million. Program and support expenses are funded by accounting support fees and by a portion of Reserve Funds, as described more fully in the Statements of Financial Position Reserve Fund Investments section below. In 2016, the FAF was able to significantly reduce accounting support fees with amounts made available from Reserve Fund balances. Since a portion of the funding came from Reserve Funds (which are not operating revenues) it resulted in the difference between net operating revenues and total program and support expenses. This difference was anticipated during preparation of the 2016 budget.

The FAF’s expenses include program expenses, which are those directly related to its sole program of standard setting, and support expenses, which are those related to the general administration and operation of standard-setting activities.

The 2016 program expenses related to the FAF’s primary mission of improving financial accounting and reporting standards. These efforts included fostering improvement and increased comparability of international accounting standards, working with the Private Company Council (PCC) to improve the standard-setting process for private companies, and continuing the development of the GAAP Financial Reporting Taxonomy (Taxonomy) for eXtensible Business Reporting Language (XBRL). It also includes the evaluation of the effectiveness of the standard-setting process through the Post-Implementation Review (PIR) process.

Program and support expenses increased by $2.1 million, or approximately 4%, from 2015 to 2016. The increase in program and support expenses primarily relates to the ongoing IT Enhancement project. In 2015, the FAF completed a comprehensive assessment of our use of technology and identification of new processes and systems to meet the current and future technology needs of the FAF, the FASB, and the GASB. As a result of this process, a long-term IT enhancement plan and roadmap were developed. In 2016 and 2015, program and support costs included $2.1 million and $300,000, respectively, related to the IT Enhancement project, reflecting the following initiatives:

- The development and implementation of an enterprise content management system;

- Initial development of a customer relationship management system; and

- IT governance and IT infrastructure upgrades.

Financial Results

The FAF’s financial statements are presented in accordance with GAAP and reflect the specific reporting requirements of not-for-profit organizations. The following is a discussion of the highlights of the activities and financial position of the FAF as presented in the accompanying audited financial statements.

Statements of Activities

The following charts display the sources of revenues and the program and support expenses for 2016 and 2015:

2016 Sources of Revenues

- 53%FASB Accounting Support Fees

- 18%GASB Accounting Support Fees

- 29%Net Subscriptions & Publications

2015 Sources of Revenues

- 54%FASB Accounting Support Fees

- 16%GASB Accounting Support Fees

- 30%Net Subscriptions & Publications

2016 Expenses

- 78%Program — Standard Setting

- 22%Support

2015 Expenses

- 78%Program — Standard Setting

- 22%Support

FASB Accounting Support Fees

FASB accounting support fees are assessed upon issuers, as defined by the Sarbanes-Oxley Act, to fund the expenses and other cash requirements of the FASB’s standard-setting activities, as reflected in the FAF’s annual operating and capital budget—the FASB recoverable expenses.

Equity issuers and investment company issuers are assessed a share of the accounting support fees based upon their relative average monthly market capitalization, subject to minimum capitalization thresholds. The FAF has retained the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB) as its agent for invoicing and collecting FASB accounting support fees. FASB accounting support fees were $24.8 million in 2016 and $23.9 million in 2015. The FAF paid the PCAOB approximately $209,000 per year for collection services in 2016 and 2015.

The Office of Management and Budget (OMB) has determined that the FASB accounting support fee is subject to sequestration pursuant to the Budget Control Act of 2011 (BCA). Sequestration amounts are based on the federal government’s fiscal year, which, for the 2016 sequestration, began on October 1, 2015, and ended on September 30, 2016. During 2016, the FAF sequestered approximately $1.77 million with respect to the FASB accounting support fee. The OMB notified the FAF that the 2016 sequestered funds were available for spending for the 2016 federal fiscal year, which began October 1, 2016. The FAF understands that the FASB accounting support fee for federal fiscal year 2017 will be subject to sequestration in a similar manner.

GASB Accounting Support Fees

Pursuant to the Dodd-Frank Act, in 2012, the SEC issued an order approving a proposed rule change to the by-laws of the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA) to establish an accounting support fee to fund the annual budget of the GASB, including rules and procedures to provide for the equitable allocation, assessment, and collection of the GASB accounting support fee from FINRA members. FINRA collects the GASB accounting support fee quarterly from member firms that report trades to the Municipal Securities Rulemaking Board (MSRB). Each member firm’s assessment is based on the member firm’s portion of the total par value of municipal securities transactions reported by FINRA member firms to the MSRB during the previous quarter. GASB accounting support fees were $8.3 million in 2016 and $7.4 million in 2015. The increase in GASB accounting support fees reflects an increase in GASB budgeted recoverable expenses for 2016. The FAF paid FINRA $30,000 per year for collection services in 2016 and 2015.

Subscriptions and Publications

Subscriptions and publications revenue for FASB and GASB product offerings are presented in the statements of activities on a combined basis, net of direct costs of $3.7 million and $4.3 million in 2016 and 2015, respectively. Gross revenues for FASB and GASB product offerings are separately displayed in the charts below for 2016 and 2015.

FASB Subscriptions and Publications (dollars in thousands)

2016

- $13,06485%License Fees

- $2,06313%Subscription Plans

- $2442%Codification Bound Volumes

- $240%Other

- $15,395100%Total

2015

- $13,28284%License Fees

- $2,15914%Subscription Plans

- $3672%Codification Bound Volumes

- $220%Other

- $15,830100%Total

The FAF licenses the content of the FASB Accounting Standards Codification® (FASB Codification) to commercial publishers and others for inclusion in their proprietary, comprehensive, online research systems. The FASB Codification also is directly accessible through an online platform and can be viewed either through a free Basic View or as an annual paid subscription to the Professional View that provides advanced functionality and navigation. The FAF also sells a bound edition of the FASB Codification and provides The FASB Subscription, an annual paid service that includes the distribution of printed copies of FASB Accounting Standards Updates (ASUs) when issued.

FASB subscriptions and publications revenues totaled $15.4 million in 2016, down 3% from 2015. License fees were down 2% from 2015 and represented 85% of the total subscription and publication revenues in 2016.

GASB Subscriptions and Publications (dollars in thousands)

2016

- $1,13367%License Fees

- $46728%Subscription Plans

- $594%Bound Editions

- $251%Final Documents & Other

- $1,684100%Total

2015

- $1,09366%License Fees

- $50330%Subscription Plans

- $422%Bound Editions

- $272%Final Documents & Other

- $1,665100%Total

The FAF licenses GASB materials to commercial publishers and others for inclusion in their proprietary, comprehensive, online research systems. GASB materials are also directly accessible online through the Governmental Accounting Research System (GARS). GARS Online can be viewed either through a free Basic View or as an annual paid subscription to the Professional View that provides advanced functionality and navigation. GASB materials also are available through various subscription plans sold directly by the FAF, including The GASB Subscription (consisting of final documents as issued) and the GASB Board Packages. In addition, the FAF sells bound editions of the GASB Codification, GASB Original Pronouncements, and the GASB Comprehensive Implementation Guide, as well as hard copies of individual Pronouncements, User Guides, Research Reports, and other documents. GASB subscription and publication revenues totaled $1.68 million in 2016, a 1% increase from the 2015 revenues of $1.67 million. License fees increased by 4% from 2015 and represented 67% of the total subscription and publication activity in 2016.

Program Expenses

The FAF’s program expenses, which comprise the standard-setting activities of the FASB and the GASB, totaled $41.1 million in 2016, a 5% increase compared to $39.2 million in 2015. Salaries and benefits increased by $866,000, or 3%, primarily due to annual salary rate increases. Salaries and employee benefits comprise approximately 81% of the FAF’s program expenses. Professional fees increased by $1.3 million primarily related to the IT Enhancement project, which directly supports the standard-setting activities of the FASB and the GASB. Other program expenses include domestic and international travel for the FASB and the GASB Board members and staff, costs for holding advisory group and other meetings, library subscriptions and other reference materials, and other miscellaneous expenses.

Support Expenses

The FAF’s support expenses totaled $11.5 million in 2016, compared to $11.3 million in 2015. The increase was largely due to a 5% increase in salaries and employee benefits costs primarily due to annual salary rate increases.